Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

For the last three years, Covid long haulers have had to become their own advocates and researchers as they lobby for recognition, funding and proper healthcare. Their knowledge has been hard-won against a backdrop of sickness. They’ve pushed through symptoms that ravaged their previously able-bodies and become the experts of their own disease.

That is why we decided that all the symptoms on this website should be written by patients, for patients. As our co-founder Jenene Crossan says “They poured their hearts, their souls and their deep determination to find just enough energy to put their experiences down for others to benefit from”.

Although we do not intend to give medical advice, the articles have been fact-checked by a wonderful doctor who is suffering from Long Covid too.

About the author

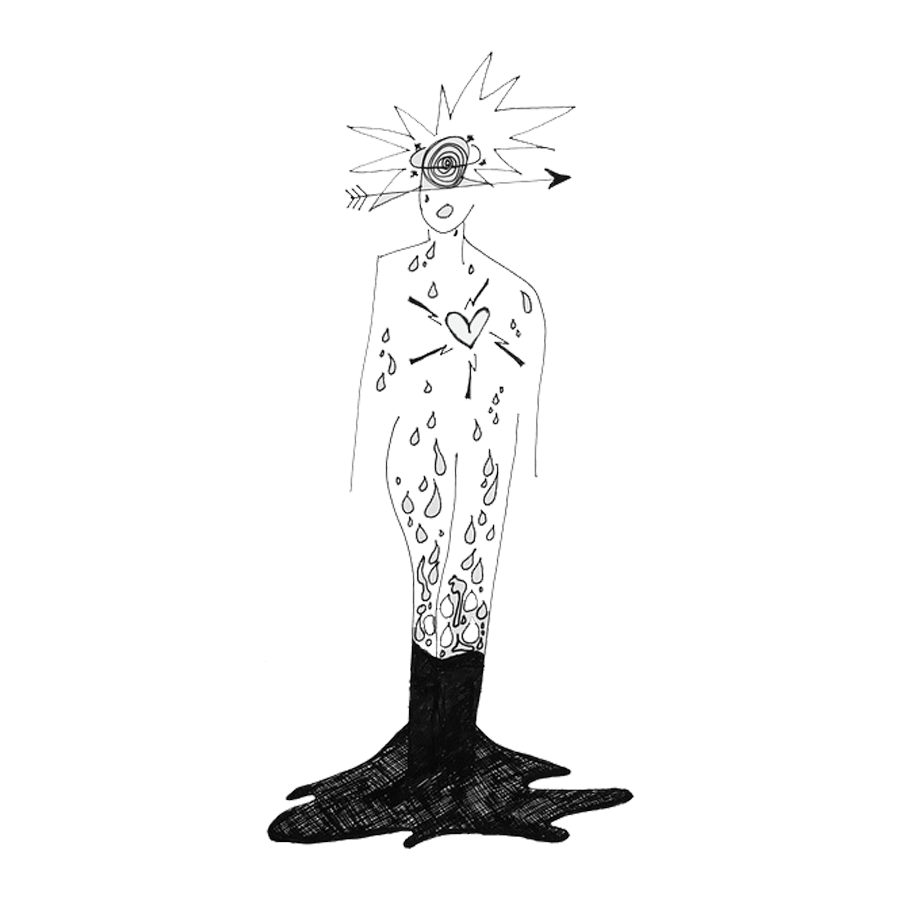

I had just turned 27 when I caught COVID-19 in mid-2022, and my infection was relatively mild. My initial recovery involved spending a week in bed watching endless Netflix series and sleeping away what seemed to be simply a nasty form of the flu. I assumed I would bounce back relatively soon. But I experienced ongoing symptoms for months afterwards, and it’s still happening today. POTS, or Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, is one of my worst symptoms.

– Male, NZ European, Pōneke/Wellington